This week’s bipartisan Senate Intelligence Committee report on Russian foreign interference in the 2016 election is the latest and most definitive case for new legislation that would help improve transparency for online political ads as a way to bolster election security. “The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 requires political advertisements on television, radio, and satellite to disclose the sponsor of the advertisement. The same requirements should apply online,” the report states. Russia spreads disinformation online through social media platforms like Facebook because they reached millions of Americans, cheaply.

“There is no reason for paid political ads running online to be treated differently than those running on television and radio — especially when the gaps in our laws are being exploited by foreign actors to weaken our country,” said Issue One Executive Director Meredith McGehee. “The conclusions of the Senate Intelligence Committee are the most powerful case to date of the Honest Ads Act. Now Congress needs to hold a hearing on this legislation.”

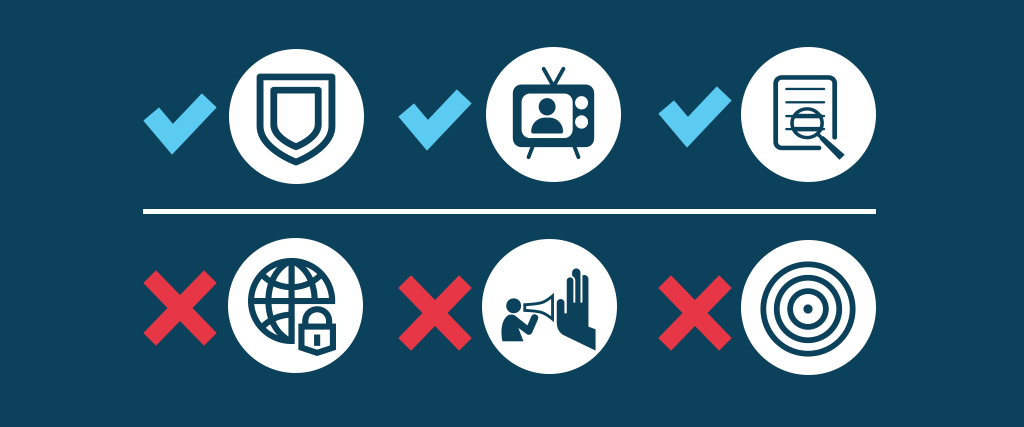

The Honest Ads Act, one of the first bills introduced to directly counter foreign actor interference in the 2016 election, would achieve exactly what the committee calls for. The legislation has 39 sponsors in the House and Senate (19 Republicans, 20 Democrats) — including Foreign Relations Committee Chair Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) — and is backed by Facebook, Google, IBM, Microsoft, Twitter, and 115 former members of Congress from both parties. Under this new legislation, the same disclosure requirements that apply to television and radio ads would also apply online, including Federal Communication Commission rules that apply to ads covering legislative issues of national importance.

The 85-page report, produced over 2 ½ years under the chairmanship of Sen. Richard Burr (R-NC), analyzes the role the largest online social platforms — Facebook, Twitter, Google, and others — played in the spread of foreign disinformation before, during, and after the 2016 election cycle. The committee’s report also calls on Congress to examine new laws to bolster election security, urges the White House to publicly address the danger of further foreign interference, and recommends government agencies collaborate more with the private sector to protect elections and stop misinformation.

“Russia is waging an information warfare campaign against the U.S. that didn’t start and didn’t end with the 2016 election. Their goal is broader: to sow societal discord and erode public confidence in the machinery of government,” Burr said in a statement. “By flooding social media with false reports, conspiracy theories, and trolls, and by exploiting existing divisions, Russia is trying to breed distrust of our democratic institutions and our fellow Americans. While Russia may have been the first to hone the modern disinformation tactics outlined in this report, other adversaries, including China, North Korea, and Iran, are following suit.”

Below are eight key takeaways from the report that support the need for greater transparency on social media platforms, and explicit guidelines of paid political advertising online:

- The problem is not over. Russia’s Internet Research Agency (IRA) activity on social media has increased since the 2016 election, when it went to great lengths to disrupt our political process. Analysis of IRA-associated accounts shows a significant spike in activity after the election, increasing across Instagram (238 percent), Facebook (59 percent), Twitter (52 percent), and YouTube (84 percent). Researchers continue to uncover IRA-associated accounts that spread malicious content. As late as the fall of 2018, Facebook continued to find activity attributed to the GRU (Russia’s military intelligence agency). [page 68]

- Russia preferred online social platforms because they reached millions of Americans, cheaply. Russia’s influence operatives have found appeal in the cost-effectiveness of Facebook pages as a targeted communications medium. [page 43]

- Russia targeted politicians in both parties — and may have directly harmed the chances of certain candidates winning office. The IRA targeted Hillary Clinton as well as Republican candidates during the presidential primaries. Senators Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio were targeted and attacked during the Republican primary election, as was Jeb Bush. [page 6]

- Russia also targeted their opponents who weren’t running for office. After the 2016 election, Mitt Romney — historically critical of Russia and who memorably characterized the country as the United States’ “number one geopolitical foe” during a 2012 presidential debate — was targeted by IRA influence operatives while being considered for Secretary of State in the Trump administration. [page 37]

- Russia’s ads did not focus on candidates. Nearly 95% of the IRA-purchased advertisements prior to the 2016 election did not mention either presidential candidate. Instead, they focused on divisive social issues to sow discord among Americans. [page 44]

- Russia targeted swing states and minority voters. The IRA targeted some election swing states, as well as areas with significant African-American populations, with advertisements that leveraged socially incendiary and divisive subjects. [page 40] About 25% of Facebook advertisements purchased by the IRA were targeted down to the state, city, or in some instances, university level. If they had used Facebook’s full suite of custom targeting tools, they likely would have had more reach and impact. [page 44]

- Social media activity turned into real-world protests. Facebook identified at least 130 events that were promoted on its platform as a result of IRA activity. After the election, IRA operatives orchestrated disparate political rallies in the United States [using social media] both supporting president-elect Trump, and protesting the results of the election. A mid-November 2016 rally in New York was organized around the theme, “show your support for President-Elect Donald Trump,” while a separate rally titled, “Trump is NOT my President,” was also held in New York, in roughly the same timeframe. [pages 42, 46]

- Online disinformation is just one foreign interference tool. Russia’s targeting of the 2016 U.S. Presidential election was part of a broader, sophisticated, and ongoing information warfare campaign designed to sow discord in American politics and society. [page 5]

The Honest Ads Act is one bill in a suite of legislative solutions Issue One is promoting through its “Don’t Mess With US” project that would stop foreign interference in our elections. Learn more at www.dontmesswithus.org.